Ez wuochs in Burgonden ein edel magedin,

daz in allen landen niht schoeneus mohte sin,

Kriemhilt geheizen; si wart ein scoene wip.

darumbe musosen degene vil verliesen den lip.

There in Burgundy a noble maiden flowered

Such that none in all the lands could equal her.

She was called Kriemhild; she grew into a beautiful woman

Because of this many warriors had to lose their livesThe Hidden Heroine

Revenge stories are usually not named for their victims. In that sense the Nibelungenlied is exceptionally poorly titled. It is Kriemhild’s birth that begins the Nibelungenlied just as her death ends it. While there is one medieval manuscript that titles the poem, Kriemhild, the vast majority still title it after the Nibelungs and interpreters have decided to focus them as the protagonists of the story. But the story, when closely examined, resembles more closely a sort of vengeance fueled bildungsroman for Kriemhild rather than a story of the Nibelungs. The poem traces her transformation from rosy cheeked princess to medieval Fury.

The modern reception of the Nibelungenlied has continued to diminish Kriemhild. It follows the Norse Saga of the Volsungs, which recasts her as an obstacle to the love of Sigurd (Siegfried) and Brynhild (Brunhild). However if we recenter Kriemhild as a protagonist in her own right what emerges is a powerful story of the cycles of vengeance, questions of identity and agency, and an inversion of our usual expectations of medieval narrative. Kriemhild is a heroine of mythic proportions. She is conventionally feminine, yes–a virginal goddess, a patient wife–but as the narrative develops so does she. She becomes a ruler in her own right, asserting power, defending her rights, and pursuing her goals with unrelenting determination. Her death comes, not as repudiation of her actions, but as a kind of apocalyptic clearing of the slate for the narratives that come afterwards. There is a sense of exhaustion at the end of the narrative much like what follows the deaths of other heroes of medieval myth; Roland, Arthur, or Beowulf. The world must go on but the world feels emptier without them. While we have to be careful not to project too much of our modern preoccupations onto Kriemhild, it is clear that the tradition is remarkably open to interpretation and reworking. We would not have Lancelot, Gawain, Mordred, or Don Quixote if it were not so.

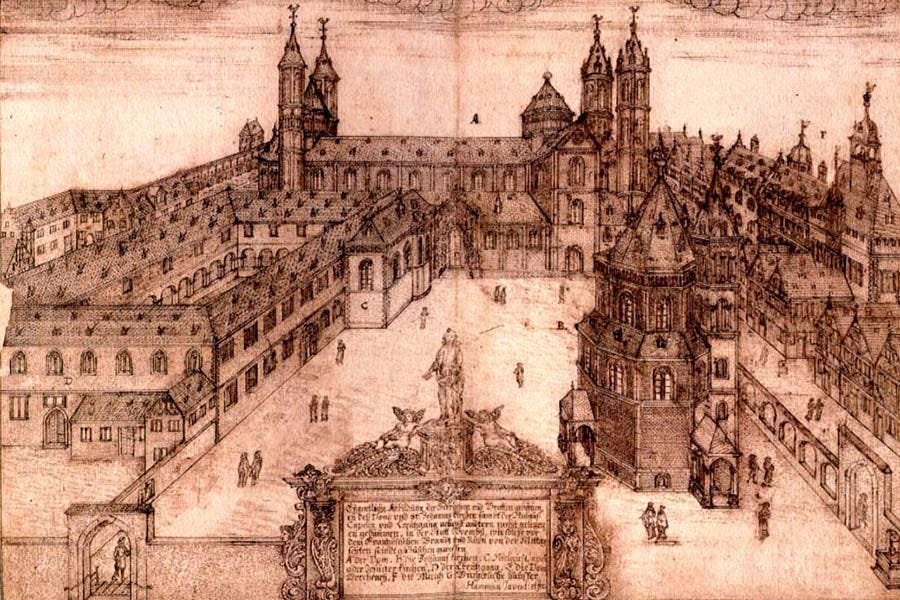

A Place of Myths

Like these later retellings of chivalric romance the Nibelungenlied sets itself in a historical-mythic middle ground. This allows the story to draw on real world locations while maintaining a narrative distance. So, Kriemhild’s early life is spent at the Burgundian court as a typical sheltered princess awaiting a doomed heroic suitor. The court is located in an identifiably real city; Worms. Siegfried, her eventual husband, on the other hand, is a Dutch prince who has his capital at Xanten, another real world city in modern-day Germany. His youth and fame comes from both historic and mythic feats. He is a dragonslayer and he acquires the magical sword Balmung. He is also a highly successful ruler whose greatest asset is the wealth he accumulated after his conquest of the Nibelungs. The Nibelungs themselves also straddle this historical-mythic line. Their name seems to be derived from one of the tribes of the Franks but they are also presented as containing both giants and dwarves. The story also seems to draw on memories of two early Frankish queens, Brynhild and Fredegund, who warred with each other for years in the 6th century. With this layering of the mythic on the historical, the story stands at a slight remove to the everyday while still being able to speak to the anxieties and preoccupations of the time.

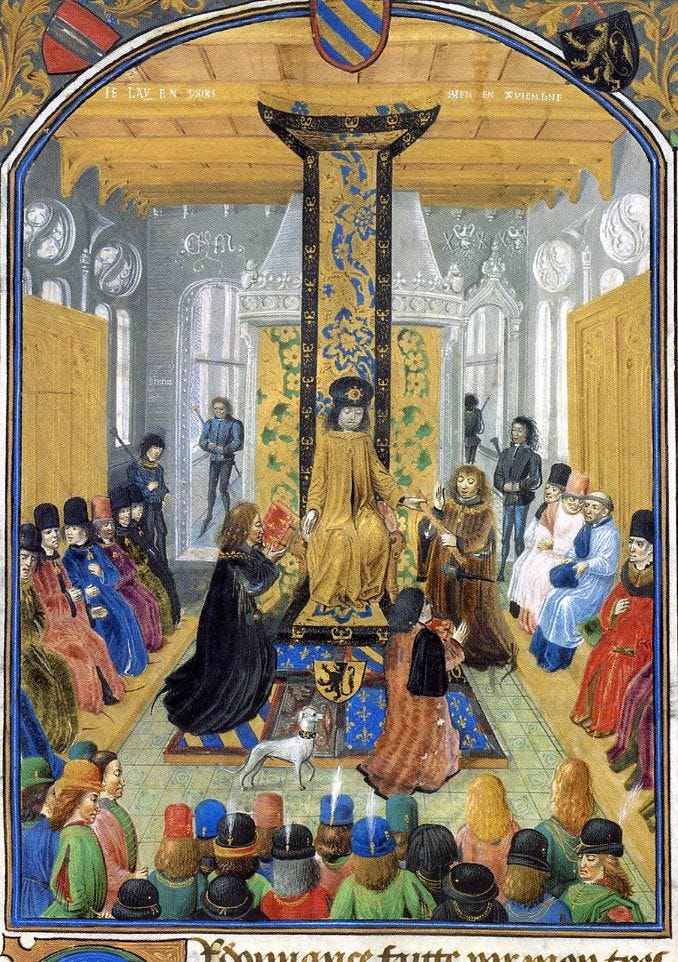

The Medieval Panopticon

The concept of the panopticon was first developed by the 18th century social theorist Jeremy Bentham and has in more recent times been used by Foucault to explain modern society and critics to discuss the effects of social media. It is also the perfect image to understand the functioning of a medieval court. Each member strives to have their identity confirmed or misunderstood by the others, either through lying or truth telling. This must be done in a public space so that the identities of the characters are confirmed by others. This is also the reason why fashion and public displays of wealth are so important in medieval narratives and history. It is the same rationale used by the French government before the Revolution, the appearance of wealth is the same as actual wealth, and Instagram encourages the use of filters. While in the medieval period, a time when wealth was tied to land and land determined power, these overt displays of wealth were shorthand for the power of the individual.

There are moments of personal narration of identity in medieval sources, but it is primarily the public confirmation or rejection of identity that matters. This collision of public identities in the Nibelungenlied occurs most obviously in the case of Brunhild and Kriemhild. The women’s rivalry reveals itself during a tournament in Worms where they argue over their husband’s supremacy. Kriemhild though is no longer the blushing princess of the beginning of the story. She and Siegfried now rule over the Dutch from Xanten and she has been given independent lands to rule and given birth to a son. Both of these mark her as not just as an independent ruler but as a successful one as having an heir is a key part of the success or failure of a lineage. So when Brunhild challenges her presumption of equality Kriemhild stands her ground against the physically dominant Brunhild. This enrages Brunhild and she decides to publicly shame Kriemhild later when they are both about to enter the church for Mass. This escalation of a private quarrel to the public sphere of the court will play on the panopticon features of the court. The public shame of such an event would be devastating and a potential crippling blow to Kriemhild if it is successful. But it is also dangerous for Brunhild as well because she will be placing herself also in full view of the panopticon court. The center of the panopticon is the center of power as it can ‘observe’ all places in the panopticon. But it is also a dangerous position as the members of the court are also looking carefully for any sign of weakness on the part of the observer. Brunhild’s accusation is carefully stage-managed to attempt to take advantage of these features, as the whole court will be present or hear of an accusation that occurs just before Mass.

However, as their rivalry comes out into the open for the whole court it is Kriemhild that delivers the most shocking blows. She reveals her ownership of Brunhild’s girdle and ring and Brunhild’s defeat at Siegfried’s hands saying; “Your fair person was first caressed by Siegfried, my dear husband. Certainly it was not my brother who won your maidenhood.” This public humiliation shatters the previously dominant Brunhild. It will also require an equally public repudiation on Siegfried’s part of the accusations his wife has made. It also marks the turning point towards Siegfried’s death.

Brunhild, to maintain any semblance of power, must escalate the conflict from there. While Kriemhild will seek to placate the other woman and avoid conflict. This attempt will occur in private, which in the panopticon of court is less ‘real’ than a public reconciliation. Also it is Brunhild’s identity and agency that has been violated. So she must attempt to reacquire them through an exertion of power which will once again allow herself to place herself at the center of the panopticon of court which Kriemhild now occupies.

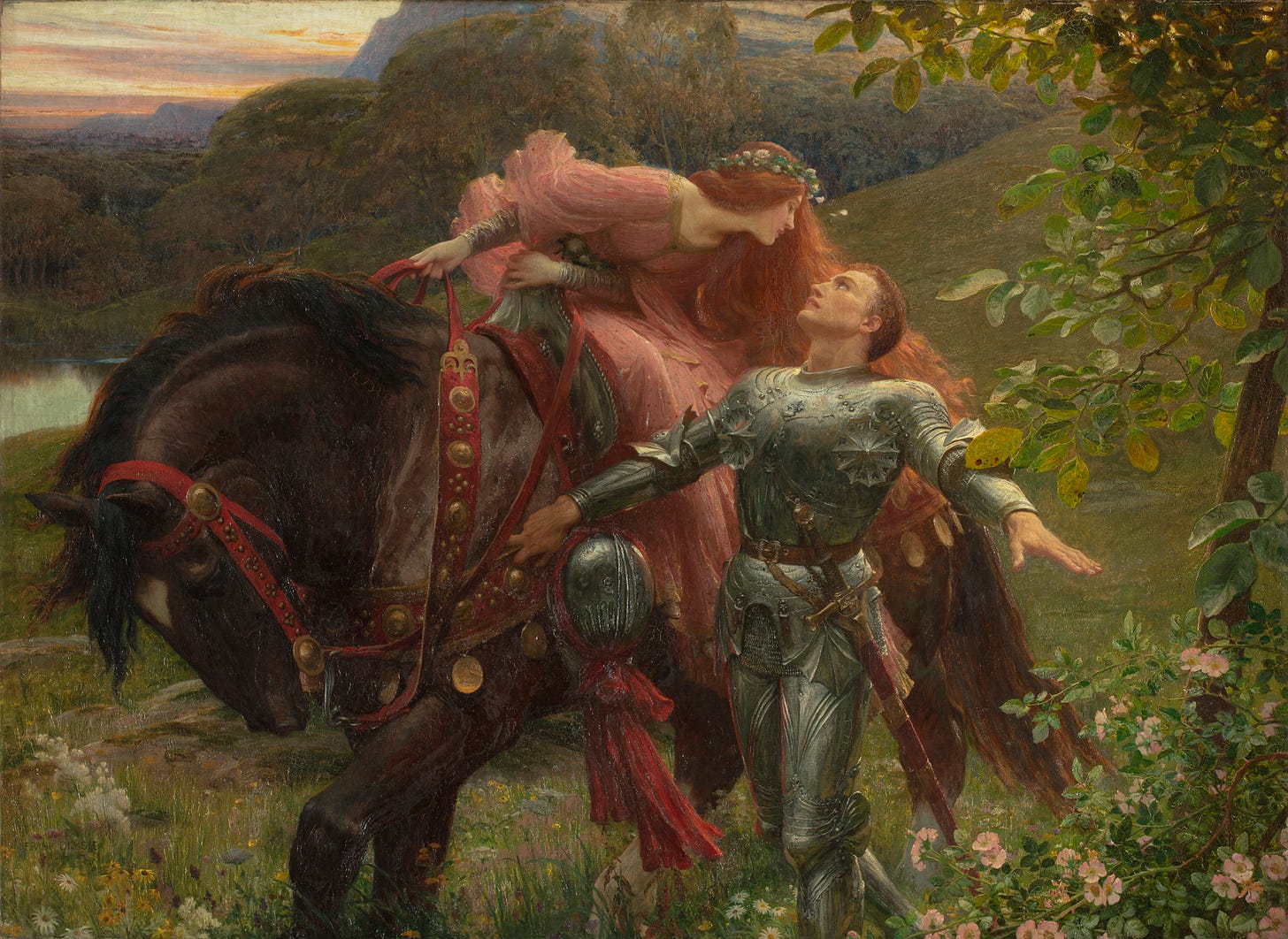

A Blushing Prince and Falconer Princess

Inverted Princess

While Kriemhild’s tragedy is foreshadowed from the outset of the story, it also subtly inverts gendered expectations. She dreams of her pet falcon being torn apart by two eagles. Falconry, while practiced by both genders, was still a male gendered activity in the medieval period, and in particular was associated with kingship and rulership. So to have Kriemhild being the falconer the story subtly inverts a traditional image.

A similar inversion happens when Siegfried is introduced to the Burgundian court. He is introduced by the minister Hagen who explains his legendary exploits; slaying a dragon, bathing in its blood to make himself invulnerable, possession of the cloak of invisibility, and lordship over the Nibelungs. Siegfried’s arrival is marked by a traditionally bold and arrogant heroic manner. And his first test is suitably masculine. A war against the Saxon and Danish invasion of Burgundy. Siegfried leads the vastly outnumbered army to victory with an equal share of tactical brilliance and personal courage. This triumph allows him to meet Kriemhild for the first time. During this meeting, rather than Kriemhild being the blushing shy maiden, it is Siegfried who plays this role, while Kriemhild confidently welcomes him. Siegfried merely “stood in such dainty grace, as if limned on parchment by a master’s art.”

He is now the object and Kriemhild the master who has rendered him such. This dramatically inverts the typical descriptions of the meetings between men and women in medieval sources. The woman is typically the object, a flower, a jewel, a city. While the man is the active role, a gardener, a merchant, a conqueror. Both are mutually infatuated by the other in this moment but the story subtly hints here that it is Kriemhild who will be the active member not Siegfried.

The Winning of Brynhild

Kriemhild’s wooing of Siegfried is contrasted with her brother’s ‘wooing’ of Brunhild, the queen of Isenstein. This is where the story begins to take a darker turn and Siegfried begins to be morally implicated because of his actions. Brunhild is another queen unmarried by her own choice, because she has not yet found her equal. Brunhild embodies physical strength and independence and demands that suitors defeat her in three trials of strength. Gunther desires Brunhild, falling in love with her mere description, but cannot hope to defeat her without Siegfried’s magical assistance. Later, when Gunther avoids the subject of why Kriemhild was married to Siegfried, Brunhild refuses to consummate her marriage. She easily overpowers Gunther and sleeps alone. So Siegfried is again asked to intervene by Gunther. This deepens his moral implication and finalizes the removal of Brunhild’s agency. Siegfried uses his cloak to become invisible and subdues Brunhild, at the end of which he removes her girdle and ring–symbols of her agency over her body and power.

These deceptions create a foundational lie that drives the rest of the story. The medieval text skims over the implications of the scene but a modern reader is rightfully troubled by them. It strips Brunhild of her autonomy through deceit and force and utilizes narrative hand waving to paper over more disturbing possibilities and realities of the event. Not only does Gunther not actually possess the strength to best Brunhild but has agreed to the violation of her agency and autonomy over her own body. Brunhild additionally believes that Siegfried is a vassal of Gunther. So, Brunhild not only is violated by Siegfried but cannot recognize Kriemhild as her equal. Brunhild’s entire sense of self and reality has been warped by the machinations of these two men.

It is these stolen symbols, the ring and girdle, that will later become key to the tragedy. Also it is in the act of transferring these symbols of power and bodily agency from Brunhild to Kriemhild that Kriemhild begins to exert her own bodily agency and power.

From Grief to Power

Brunhild’s attempt to challenge what appears to be Kriemhild’s source of power and identity; Siegfried. Hagen provides himself as the instrument of Brunhild’s vengeance, bridging the male and female worlds and acting as a catalyst for the escalating tension. He visits Brynhild and reveals a loyalty that aligns as much to Brunhild’s wounded pride as to Gunther’s kingship. His particular brand of loyalty is echoed in knights whose motivations blur the lines between the personal and the political such as Lancelot. It also highlights him as an agent of disruption. All of his actions push the plot forward. Gunther is enticed to agree to the plot because of the temptation of seizing Siegfried’s lands. Hagen then sets about the conspiracy to murder Siegfried.

He engineers a false war to worry Kriemhild about her husband’s safety. He then visits Kriemhild who is guilt-ridden and has been beaten by an enraged Siegfried. In this traumatized and confused state Hagen extracts the single spot on Siegfried’s body where he is vulnerable. The false war is abruptly resolved and a celebratory hunt is arranged. Brunhild has completely disappeared from the story at this point, the last piece of her agency and power given over to Hagen and his schemes. Kriemhild though becomes suspicious and tries to warn Siegfried of the danger, but their ability to communicate has irreconcilably broken. After raising his hand against her he is no longer the blushing knight and the arrogantly confident tragic hero emerges.

During the hunt Hagen directs Siegfried and Gunther to a nearby spring and away from prying eyes. And when Siegfried kneels to drink, Hagen drives Siegfried’s own spear through his back. His final words are to curse the Burgundians for their treachery and to lament for Kriemhild’s coming sorrow. While Burgundian knights are appalled by what Hagen has done and feverishly try to concoct a cover story, Hagen remains determined, declaring,

““I care not if it is known to [Kriemhild], for she has shamed Brunhild’s heart. Little does it trouble me however much she weeps.”

Kriemhild will weep over Siegfried, which Hagen ensures by dumping Siegfried’s body in front of her door, her power does not diminish. Instead it will grow. She acts decisively, rallying the Nibelungs and Siegfried’s father Siegmund. The Nibelungs call for immediate vengeance but Kriemhild calms them and ensures that they return to the Netherlands, to defend it against Gunther’s attempt to conquer it. But most importantly for her power and independence she is granted the hoard of the Nibelungs as her bride gift, as even the dwarf Alberich, the guardian of the hoard, acknowledges her supremacy. She has fully transformed from the passive princess and wife to decisive political and military leader.

She remains in Burgundy putting the hoard of the Nibelungs to work immediately to continue to build her influence and power. She does this by giving gifts to nobles, supporting the poor and needy, and giving endowments for masses and monasteries. In this way she supports the three pillars of medieval society, the nobility, the commons, and the Church. Through her generosity she begins to acquire followers among all classes. This unsettles Hagen who appears to have considered Kriemhild no longer a threat after Siegfried’s death, hence his disdainful treatment of the hero’s body. But Kriemhild has found an alternative path to power, one not typically taken by women in medieval literature, through her material independence from any man. Where Siegfried relied on military conquests and personal valor, Kriemhild wields her inheritance and position with just as great an effect to subvert expectations and traditional power dynamics.

Hagen grows anxious as Kriemhild’s power continues to grow so he persuades Gunther to confiscate the hoard. This is a naked attempt to put Kriemhild back into a subservient and powerless position. She cannot continue to support her followers and they abandon her not out of disloyalty but in need of support. The hoard itself is thrown into the Rhine to keep it from anyone’s hands. But all this does is delay Kriemhild’s revenge, as she continues to look for ways to exact it even as her accumulated power slips from her hands.

The Queen’s Apocalypse

The opportunity would come when Etzel, the king of the Huns, loses his wife, Helca. The marriage offer–along with Etzel’s vassal Rudeger swearing loyalty to her–gives Kriemhild a new way to build her power beyond Hagen and her brothers’ reach. In the 13 years that she spends at the Hunnic court Kriemhild emerges as a woman who has mastered both the subtleties of court politics and the brutal requirements of revenge. She has become the unifying figure in a court. Her transformation is complete when she can summon her brothers and Hagen to Vienna for what is framed as a feast of reconciliation. It is now Kriemhild’s chance to play the master manipulator and true power behind the throne. The warnings they receive play on the epic tropes of fate and tragedy, everyone can see that the tragedy is coming, but no one can stop it. The most explicit warning comes from Dietrich von Bern, one of Kriemhild’s own vassals, but Hagen spits back

“Let her weep a while, [Siegfried] has lain dead for many years.”

When the Burgundians arrive threats begin to fly immediately. Hagen, who is carrying Siegfried’s sword Balmung, refuses to surrender his weapons and his example is followed by the other Burgundians. Kriemhild enters the hall flanked by 400 of her retainers. She is completely transformed from the budding princess from Worms, fully resplendent in her crown and gold-trimmed clothes. This is Kriemhild in her full power. .In this open display of power she has now fully eclipsed Brunhild. The Burgundian minstrel even comments that he had never seen such a warlike queen. Kriemhild understands the courtly panopticon where identity, agency, and power are all exercised through visual displays of power and wealth. So she wields her identity as Siegfried’s widow and Queen of the Huns like a weapon.

Kriemhild confronts Hagen again and publicly accuses Hagen of murdering her husband. Again the escalation from private to public accusations is played out, this time with Kriemhild being the accuser. Whereas Hagen proudly claims to have killed Siegfried because of the insult to Brunhild. But he also understands the public nature of the conflict and challenges anyone who will avenge it then and there.

But the killing will not start in the hall. Instead it will start outside the main hall and rush into the room like a backdraft. A Hunnic prince harasses a Burgundian over serving a murder. The Burgundian, who is Hagen’s brother, lashes out at the insult and beheading the Hunnic prince. The Huns rush Hagen’s brother who retreats into the main hall as he and his retainers fight off the enraged Huns. He bursts into the hall covered with other men’s blood as his men are slaughtered outside. Hagen is told what has happened and turns to his Hunnic host and says:

“Now let us drink to friendship and pay for the royal wine. The young lord of the Huns shall be the first.”

With this he beheads Ortleib, the young Hunnic prince and child of Kriemhild and Etzel. Chaos erupts in the hall as the Burgundians begin to kill the Huns. None of the Huns are armed so they must grab benches and chairs to attempt to defend themselves. The Huns are driven out of the hall and the Burgundians take up defensive positions. The siege that follows compresses the whole Trojan War into a few days as Hunnic heroes throw themselves at the slowly tiring Burgundians. The hall is set alight and as the flames slowly consume the building. As the flames, the fighting carry on the poem swerves into increasingly apocalyptic imagery. The Burgundians, growing thirsty, drink the blood of the slain so that they can continue fighting. A nightmarish reflection of Siegfried drinking from the spring. Rudeger is slain and his body displayed to the Huns crucified on a pole. The scene echoes the death, humiliation, and ransoming of Hector’s in the Iliad. Kriemhild here plays the role of Priam and Hecuba simultaneously, leading the mourning for Rudeger and also attempting to ransom the body back.

Even though the Burgundians are begged for the return of the body, they refuse. Because of this insult the men from Berne, who have been neutral so far, intervene. Finally there are men to match and defeat the Burgundians. Folker is the first Burgundian to die. And as the fighting drags on the bodies pile up as men-at-arms and kings begin to die. After a rush of violence only Hagen and Gunther are left and they are taken hostage and surrendered to Kriemhild. She demands from Hagen the return of what was taken from her. When he refuses because of his oath to Gunther, Kriemhild orders her own brother beheaded. This is done without question and she shows Hagen her brother’s head. Hagen laughs.

This is traditionally read as her demanding the hoard of the Nibelungs, and Hagen’s later claim of only him and God knowing where it is seems to indicate that Hagen understands this to be the case. But there is much else that Hagen has taken from her that the hoard is only a symbol of. He has taken a husband, a child, power and influence, and her loyal retainers. And the only thing that she explicitly mentions that he has taken from her is Siegfried. It seems that Kriemhild is asking for the impossible, knowing that it is impossible. Hagen for his part either seems to purposefully misunderstand, or–as a final failure of his character who is originally presented as understanding everything–genuinely misunderstands that the demand as impossible. When he offers his final mocking refusal she does take two things from him. First is the sword Balmung, the second and final is his head. So for the first time Kriemhild will fully take up the masculine role and directly use violence herself. As a woman in medieval society she has needed retainers and vassals to use violence for her, up to this point. But in this final moment she does the deed herself. Etzel is terrified of her, reduced to blubbering about the death of Hagen at the hands of a woman. One of Dietrich’s vassals is moved to rage at this. He strikes and cuts the queen in two.

Echoes Across Stories

The narrative, through its inversions and questions of agency, asks age old questions and does not provide clean answers to them. They are questions that echo through medieval literature and modern literature as well. It presents us with a woman shaped by her circumstances and seeking to overcome them, and the violent reaction to her when she does so. The narrative shows us how violence and jealousy turn back on themselves and create a cycle of violence that can devour all involved. And it presents us a death that is heroic, tragic, and disturbing all at once.

Kriemhild’s death, though is largely unique in medieval literature, parallels two other proto-typical medieval heroes–Roland betrayed by his uncle and Arthur betrayed by his son. All three deaths involve a betrayal of multiple fundamental relationships, both familial and vassal. All three deaths also mark the end of an era. Roland’s death leads to the decline of Charlemagne’s kingdom. Arthur’s death sees the breaking of the Round Table and the loss of Camelot. Kriemhild’s death sees the Hunnish kingdom crippled and the Burgundian kingdom without a monarch. The world is emptier with their deaths. The lack is felt by the characters in all of the narratives as they are left circled around a corpse, lifeless and unmoving themselves. The Nibelungenlied closes with the image of blood-soaked men around the corpse of a queen with Balmung clutched in her hands. She is no longer the rosy cheeked princess that opened the poem.

Fascinating take on Kriemhild's agency. I always thought when Hagen says, “Little does it trouble me however much she weeps,” that it was a sign of his psychopathy, ha ha.