Among the fragments that had to be cut from or avoided entirely in my essay about Ibn Khaldun and Adam Smith was any exploration of the figures around them. In particular, an examination of other political economists who interacted with Smith and the rulers who Ibn Khaldun served as a scholar-politician. What follows is a summary of the life of Mohammad V of Granada and the role that Ibn Khaldun played in his court. Also a discussion of Pedro IV “the Cruel” whom Ibn Khaldun visited on a diplomatic mission. And finally some wild speculation as to how this meeting might intersect with Ibn Khaldun’s thoughts in the Muqaddimah.

Muhammad V becomes quickly interesting because he has two different reigns. Rulers who manage this are not always effective but always interesting. Æthelstan Unræd and Mehmet II share this distinction with Muhammad. Muhammad was born on Jan 4th 1339 to the Sultan Yusuf I and the slave concubine Butayna. He had a younger sister and two half-brothers and 5 half-sisters. He was the eldest and was being groomed for rule when his father was murdered on Oct 19th, 1354. The perpetrator was described as a “madman” and had attacked the sultan at Friday prayers. This event catapulted Muhammad into rulership as a 16 year-old. Because of Muhammad still being a minor and his lack of practical experience a sort of regency council developed made of the hijab, the vizier, and the commander of the Ghazis. The vizier would create a loyalty oath which the major officials and governors would have to swear to uphold.

This vizier’s name was al-Khatib and was a close friend of Ibn Khaldun. He would become one of the most important intellectual forces in the sultanate. When he fell from grace and was executed it would trigger Ibn Khaldun’s self-imposed exile, writing of the Muqaddimah, and flight from North African politics.

Muhammad’s first reign was dominated with concern to maintain and normalize relations with the surrounding Christian kingdoms and Muslim sultanates. His relationship with Castile remained cordial, cooperative, and somewhat subservient. He would pay tribute and provide military support when requested. This relationship was also important to Castile as they sought to consolidate and expand their power in the peninsula. Their primary antagonists in this venture were other Christian kingdoms on the peninsula namely; Portugal, Aragon, and Navarre. It would be these antagonists and the ongoing Anglo-French war which would eventually draw both French and English armies into the peninsula.

Muhammad also sent Khatib to the sultanate of Morocco, capital in Fez, to ensure there was peace between the two sultanates. This was necessary as both claimed descent from and rights to the past Andalusian caliphate which had ruled most of Iberia. These kingdoms were traditionally, if not at war, then locked in direct competition. They all claimed a similar inheritance, a similar legacy, a similar cultural continuance. This was the reason that Muhammad would send Khatib to negotiate. Despite these efforts however, the Marinid Sultan Abu Inan could or would not help Muhammad keep power when a palace coup placed his half-brother Isma'il on the throne in August of 1359. Muhammad V initially had support from the town of Gaudix and its local garrison. This garrison would not be enough to retake the throne and so Muhammad V would flee to the Marinid sultan in Fez, Morocco.

Rise of el Bermejo

Isma’il only ruled for less than a year, being murdered himself by his brother-in-law who would become Muhammad VI. He would be referred to by the Spanish kingdoms by the moniker el Bermejo (The Red One). The Muslim chroniclers would also accuse him of tyranny and being a coarse man in dress and manners as well as lacking in oratory skills. He reportedly had a tic that moved his head right and left uncontrollably. According to Ibn al-Khatib, who had little reason to be sympathetic, he had a hashish addiction. He in particular was afraid of Muhammad V returning and persecuted those whom he suspected of sympathizing with the exiled prince. Many at court fled Granada to Morocco or to the Christian Crown of Castile. He would strike a deal with the Marinid sultan to prevent Muhammad V from returning and in return he would arrest Moroccan princes who fled from the Marinid sultan.

Muhammad VI would then also break the alliance with Castile and instead ally himself with the Aragonese crown. He would join the War of Two Peters on the side of Aragon. This war would eventually be the war that the English and French troops would join. It had begun in 1356 and would continue until 1375. Muhammad VI’s role in the conflict would not last that long. Castile, under Pedro “the Cruel”, would take the initiative after agreeing to a peace with Peter IV in May 1361. The war would turn against the Granadans, but also specifically against Muhammad VI. Pedro pressured Abu Salim the Sultan of Morocco to allow Muhammad V to return to Granada by threatening to attack Marinid possessions on the Iberian Peninsula. Muhammad V did not let this go to waste. It would not be an easy war. It would be a grinding one. But by 1362 the steady grinding meant that Muhammad VI no longer felt secure in Granada. The grind had also ensured that the people of Granada had turned against him. Fearing death at the hands of his people or his brother-in-law he would flee Granada on 13 April 1362 with most of the royal treasury.

He would flee not to his ally in Aragon but to the king of Castile. Muhammad VI would offer to serve Pedro as his knight and to rule Granada as his vassal or to enter exile overseas. Pedro would decide instead he would rather have Muhammad V in his debt and arrest the whole group and have Muhammad VI executed by being tied to a stake. The king of Castile himself was supposed to have personally struck Muhammad VI with a lance shouting “Take that for causing me to get a bad deal from the king of Aragon!” Muhammad VI would reply in Arabic “What a little deed of chivalry.” Two other motivations are given for the murder, the Castilian chronicler de Ayala says it was because of the treasury, while Khatib says that it was because of his support for Muhammad V. But the result was outrage in the Castilian court because of the betrayal and a weakening of Pedro’s increasingly tenuous hold onto the throne. Pedro would send Muhammad the severed head of his brother-in-law as a sort of coronation present. Muhammad had entered Granada and taken up residence in the Alhambra only three days after his rival had fled.

Return of the Lion of Granada

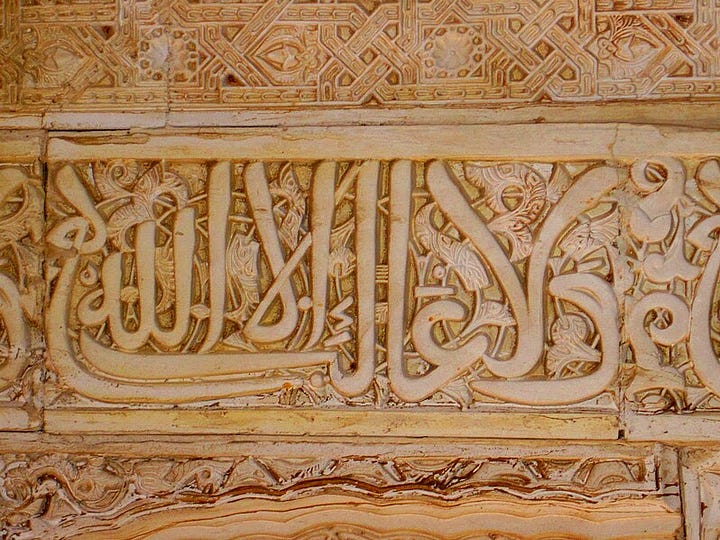

This rule would be much longer, 29 years, and end only with Muhammad V’s death in 1391. The length of his rule helped to catapult Granada to new great heights. He would be capable first through Khatib and then through Ibn Zamrak to attract some of the greatest scholars to Granada to serve in his court. Ibn al-Khatib’s downfall would be part of this developing culture as he was accused by the judges who served Muhammad and by Ibn Zamrak of being a Sufi heretic who broke with the authorized forms of worship. Khatib would flee Granada in 1371 with his eldest son but be killed in a Moroccan jail in 1374 likely with Muhammad’s knowledge if not explicit orders. Ibn Zamrak would take over Khatib’s role as vizier and play a role in the expansion of the Alhambra. This would include the carving of some of his poetry onto its very walls. Much of the current magnificence of the Alhambra would be built during Muhammad V’s second reign. Included in these expansions was the Palace of the Lions, named that because of the fountain supported by 12 lion statues, which housed the royal family’s private quarters. The Corral del Carbon, a new center for commercial and merchant activity, was also built during Muhammad V’s reign. This was part of a broader push to support the mercantile classes of his kingdom. Less beautiful but more useful additions were made such as new storage yards, commercial buildings, and secondary ports were all added to or completed anew. This focus helped Granada to increasingly become a hub for the Mediterranean and Atlantic trade networks. As the kingdoms of France and England or the republic of Flanders sought to expand their trade relationships with places like Genoa and Venice who could connect them to the Silk Road, Granada became more and more vital for these traders.

Nor was it just trade that Muhammad V excelled at and continued the policies of his father. He also reaffirmed the alliance with Castile and even signed a new treaty with Aragon. Though it does not appear that he ever dealt directly with the kingdoms of England or France he had to navigate the fall out of their rivalry and ongoing conflict. When Bertrand du Guesclin entered the Iberian peninsula with the masses of the Free Companies he had in theory recruited them to fight a crusade against Muhammad V. This crusade was likely just an excuse to help export the pillaging Free Companies but still required Muhammad to move carefully to prevent it turning into something more real.

Khaldun as Diplomat and Scholar

Playing a key role in these negotiations and diplomacy was Ibn Khaldun. Khaldun had joined the royal court in 1362 as Muhammad had made his triumphant return to Granada. There he joined his friend al-Khatib and proved himself to be an able advisor and diplomat. The two had likely met in Fez, where Khaldun served the Moroccan court and Muhammad V was in exile. It was Khaldun who would be sent to negotiate the alliance and treaty between Castile and Granada in 1364. While we do not have a detailed breakdown of the negotiations we can infer that Pedro was impressed with his Muslim guest. He also seems to have learned or been told about Khaldun’s claim to properties in Castile as he attempted to use these properties to lure Khaldun to his service. He offered to restore Khaldun to these properties as well as a place in his court, if he would agree to convert to Christianity. The pious Khaldun refused and returned to Granada. However, cultural exchange did not stop as Pedro’s palace at Alcazar was being redesigned with the help of Granadan artisans. And it is clear that the redesign of the Alhambra utilized Castilian artisans and Christian motifs and architectural practices. Pedro would have little time to enjoy this exchange as it was only two years later that his half-brother Henry of Trastámara and Bertrand du Guesclin marched into Castile and Pedro was overthrown. This war would ebb in Pedro’s favor when the Black Prince intervened on his side, however, the ultimate result would be Pedro’s death at the hands of his brother in 1369. By that time Ibn Khaldun was just about to start his work on the Muqaddimah, after leaving Granada and re-entering North African politics.

Speculation in light of the Muqaddimah

I wonder if anything that Ibn Khaldun saw in Pedro’s court informed or filtered into his Muqaddimah. The Castilian court, like the Granadan and North African courts, was filled with intrigues, rivalries, and potentially deadly political games. Khaldun does not explicitly reference any impressions of Christian kingdoms, and they are barely mentioned even in his survey of world geography, but I wonder if we see not just the North African courts but also the Castilian court in his discussion of asabiyyah failing, and the separation of the ruled from the ruler through needless titles and positions. I also wonder if part of the reason that Khaldun refused Pedro’s offer was more pragmatic than religious. Did he see in Pedro another Muhammad VI? A man who was systematically making himself weaker through the cruelty which he confused with strength. Did Khaldun’s appreciation for the usefulness of history signal to him, in any way, that Pedro was a man who was on the edge of failure? Pedro “the Cruel” and Muhammad VI “el Bermejo” are remarkably similar in some ways. Both men had rivals to the throne who were exiled to neighboring kingdoms. Both were eventually overthrown through the intervention of outside powers. And both men were ultimately killed through some sort of treachery.