With the basics covered in Mesopotamia we can move to the standard comparison that it made with its tumultuous and roiling history; Egypt. If you have not read the first Lecture please find it here.

If you do not mind reading things out of order, or have already read the first one please continue onwards.

Egyptian history is presented as a regular series of cycles that rise and fall with all the regularity of the Nile’s floods. Mesopotamia on the contrary–I hope I have a small sense of this from our whirlwind of a lecture last time–is seen as far more kinetic. It is more troubling as people come and go from the stage, some settling or leaving permanently and some simply passing through. Cities rise, fall, rise again and fall again. It is an apocalyptic setting of fires that reach to the sky, men who veer too close to the animal, statue-gods who look on at a world that swirls like a maelstrom with them at the becalmed center, if only for that moment. It is a story of survival despite the conditions.

Two Lands, One Crown

Egypt is a story that is presented as an idyllic survival because of the conditions. The Nile, unlike the Tigris and Euphrates, does not flood unpredictably but predictably. Canals and damming are still monumentally important to past and present Egyptian culture, but the people are working with the river and not to survive it. Now this is a simplistic view, and with any simplistic view we must be careful in how we use it and how much we buy into it. We should only allow it to exist if it is inherently useful. If the paradigm is useful and we constantly remind ourselves that it is a paradigm and not inherently real, then we can safely use it. But we must remind ourselves of when the paradigm fails and acknowledge that it is not perfect. So, with those caveats in our mind, we will briefly explore Egyptian order. In Mesopotamia we learned about statue-gods, writing, languages, humans challenging nature, and the emergence of law codes and warlords. In effect we saw a society establishing its required aspects, what Georges Dumézil called the tripartite society of priests (who pray), warriors (who conquer and protect), and farmers (who produce all the necessities).1 This of course is a paradigm and while useful cannot be taken too far and has received reasonable criticism from people such as Cristiano Grottanelli, and Benjamin W. Fortson cautioning against taking such an interpretation too far.2 In Egypt we should notice similarities with Mesopotamia; law codes, connection between gods and nature, and rulers tying themselves to gods. However, the details matter.

The periods of Egyptian immediately are delineated very differently from Mesopotamian history. Mesopotamian history charts its course from the dominant city-state, kingdom, or empire. Because it is such a diverse region it makes sense to mark history in this way. There is not a unified Mesopotamian kingdom that it would be useful to track dynasties from. This is completely different in Egypt because its defining characteristic is its claim to continual rule from ~3100 BC onwards. And so, the broad view of Egyptian history is divided into Kingdoms and Intermediate periods.

These will begin to break down after the Persian conquest of Egypt in the 500-400’s BC but everything in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Levant, and Greece broke down during the rise of Persia. But before ~3100 BC Egypt was actually divided into two kingdoms; Upper and Lower Egypt. And now comes the time when I have to say what every ancient history teacher has to say. Egyptian culture was dominated by the Nile. So, they did not think of geographic directions the same as we do.3 They decided geographic direction by the flow of the Nile, so Upper Egypt is in the south, and Lower Egypt is in the North around the delta. This is the exact opposite of what we expect from those names. This will be on the test.

A king of Upper Egypt named Narmer might have been the first true pharaoh of Egypt. He seems to be the first one to have united the two halves of Egypt into one political unit, though our records are somewhat contradictory on this point. He and a figure named Menes seem to in some records to share some honor, and some sources identify them with each other. This is often what happens with ancient founding characters, they become mixed with the myth of the places and overtime history and myth become welded together. This is why the projects of historians and mythographers so often intertwine.

And why the poet M. Ferrer once said, “Even if it is not true, you need to believe in ancient history.” No matter how it actually happened, and that is for a far more intensive discussion of this problem, the kingdom of Egypt was united sometime around 3100 BC. In doing this eventually a single crown was made for the pharaoh, combining the red and white crowns of the previous successor kingdoms. And this is how the distinctive pharaonic tiara was brought about and is so iconic that it is used in most depictions of pharaohs.

Another sign of this unified Egyptian kingdom was the establishment of a new capital city of Memphis. Just as the fledgling United States government sought to craft a separate identity from the two governments that had come before it by creating a new capital from scratch, so too did the Egyptian monarchy set the precedent and understood the power of a new city for a new government. Now this city was not actually called Memphis. That was its Greek name. The Egyptians called it Ineb-Hedg, and several other names throughout the thousands of years it has existed. But the original Egyptian name meant “white walls,” probably referring to the walls of the palace and major temples that came to be located there. The Greek name came about because one of those several other names specifically; Men-nefer meaning enduring and beautify. An appropriate name since the city had at that point stood for well over two thousand years in various forms. The Greeks localized it into Memphis, which Hesiod in typical syncretic fashion explained this as the name of a daughter of the river god Nilus. This river goddess then married a son of Zeus who out of love of his wife named the city that he founded after her. This twisting etymology highlights a few interesting points.

I find it endlessly interesting and disorientating to learn about how names of places and people are assigned and what different cultures name the same thing. There is an odd sense of embarrassment to feel like you have been calling a city, nation, or person that you thought you knew by something that the inhabitants or culture of which has a completely different name for. We in the English-speaking world have thousands of examples to pick from for this sort of disorientation.

The Meaning of Monumentality

But however the city of Memphis was founded, by Narmer, Menes, a son of Zeus, or by some composite of all of these things the new capital of the Egyptian kingdom would stand as a new center of political and religious life of Egypt. Cities like Cairo, and Alexandria which we traditionally associated with Egyptian power and culture could only arise on the foundations built by the antiquity of the rest of the kingdom. But in the Old Kingdom, which was inaugurated by Narmer/Menes began two of the most important paradigms that dominated Egyptian culture till the coming of the Persian and then Greek invaders; monumentality and god-kings.

The monumentality is literally the most visible of the characteristics of Egyptian culture to us in the modern day.

Monumentality is about bigness. Specifically, the bigness of buildings and art. Pyramids, obelisks, tomb complexes are all about this idea of monumentality. That things need to be distinguished, rise above and beyond what is normal. The first attempts at pyramid building met with the problems of geography, Egypt being essentially one massive floodplain that is not conducive towards heavy buildings resting easily. The ground tends to deform under their weight and cause the structures to become unstable and potentially collapse. So, the Egyptians began with stepped pyramids, then began to experiment with true pyramids. The first few attempts were awkward, like the Bent Pyramid of Sneferu. But they eventually began to routinely create the perfect triangular pyramids that we associate with Giza.

These pyramids were not just idle creations, they were tombs and monuments of the pharaoh’s power. The greater, the more geometrically perfect the pyramid is the more powerful the pharaoh. They were also religious sites, precisely oriented towards specific stars to act as conduits between the living, the dead, and the gods. As these creations grew greater it also mirrored a growth in the temple complexes and the complexity of the bureaucracy of the Egyptian kingdoms. There was most likely a fairly direct relationship, as the bureaucracy grew more able to manage the large Egyptian kings so were the kings able to prevail upon their subjects for greater and greater tombs. Of course, this was a relationship that grew over a period of roughly five hundred years, and with the most famous pyramids at Giza being built over a roughly sixty-year period between 2550 - 2490 BC.

So, it took roughly half a millennia for the Egyptians to develop this bureaucracy and the economy to the point of building a structure like the Pyramid of Khufu, which is the Great Pyramid at Giza. Five hundred years, about ten generations from the early mastabas tombs of the pre-kingdom period to the great pyramid period. After this period the pharaohs never lost their desire to build monuments, but they changed focus from massive pyramids to temples, monuments to battles or achievements, or public works.

Of course, the Egyptian desire to build monumental architecture is not uniquely Egyptian. All cultures contain some form of this desire for remembrance. All cultures create their form of monumental architecture, the massive statues of Buddha created by Buddhist cultures, the Shinto temple complexes, Christian cathedrals; all of these are examples of the same drive that drove Egyptian pharaohs to order the construction of massive tombs. Their tombs are not even the largest that have been created or the ones with the likely highest human cost; Emperor Qinshihuang, the first Qin emperor’s Mausoleum with his massive army of terracotta soldiers and supposedly mercury rivers and sea and supposed mass execution of concubines and craftsmen easily competes with Khufu for massive funerary monuments.

Chthonic Intrusions

The reason that Egyptian pyramids seem to capture our attention more is their strangeness, not because of scale though that is intimidating but because of something more quintessential. The Qin Emperor built his funerary, chthonic world in reflection of the upper world, and with the decency of a new chthonic entity had it hidden away.

Tombs so rarely have the nerve to pierce out into the sunny upperworld. They hold their special revelations downwards, in towards that misty, shadowy hidden world of the dead. Tomb complexes, and stele–which tombstones are the modern echo of–remind us living souls of the existence of a condition that is not life, but they are understated. Adventures into such an underworld must go looking for it; Orpheus must go singing, Aeneas with a potentially lying parent, even normal seekers after mysteries must descend into the earth to meet with the Oracles. All the while these seekers, even Sun Wukong, must be careful and “Know Thyself,” which as Peter Green points out was more likely to be a check on arrogance than a call for introspection.4

‘Know that you are mortal, that you are not a natural denizen of this place.’

This principle is equally true for Enkidu as it is for Izanagi searching for his dead wife Izanami. The dead hide away, and you must prepare to meet them, or you will be trapped or rejected. Not so for Egyptian pharaohs. They built their funerary complexes in such a way that they could not be missed. They impose themselves in play and striking views of all of the living world to see and contemplate. The chthonic refuses to go unseen when it comes to the Egyptian kings. No wonder mystics and the like have obsessed over the pyramids and the Egyptian hieroglyphics sure that such a special people had unlocked the secrets of the universe, both seen and unseen. That behind those strange symbols lingered knowledge that would transcend the ages. No wonder people are convinced that these things could not have possibly been built by humans, safer to assume that it was aliens than contemplate that humans raised these funeral complexes to their dead and left them so exposed, like a raw nerve.

This is of course to ignore the rampant racism and orientalism that goes into much of these ideas, but it is important to think of these things and why other similar structures do not elicit such thoughts as the Egyptian pyramids.

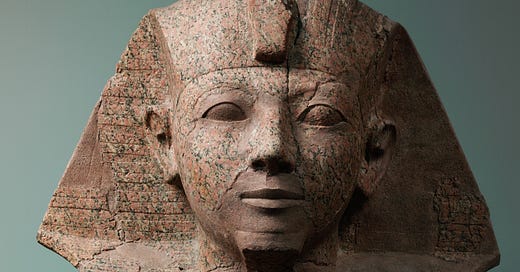

But of course, the Egyptian pyramids were not the only source of monumentality that Egypt contained. Another is its statuary. The Egyptian art style remained incredibly formalized and rigid throughout most of Egyptian ancient history, with only slight innovations and changes of posture, form, and symbols existing until Hellenism washed over them with the rule of the Ptolemies. But it is here that it is important that we highlight another interesting juxtaposition between Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Mesopotamia as you will remember statues were gods, and the kings acted as connections, diplomats for divine decrees; such as Hammurabi claimed to do in his law code stele and Moses claimed to do for the Jewish God. In Egypt the statues of gods breathed, because the pharaoh’s were gods in their own right.

Pharaohs as Gods

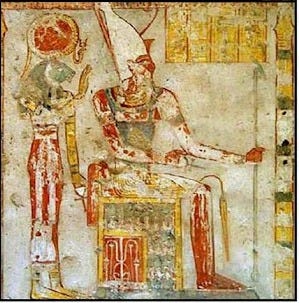

Now the exact mechanics of this relationship changed and shifted through the centuries. Sometimes they were the personification of a particular god, sometimes the incarnation, and in one particular moment they were the bride of the god. But each and every pharaoh when performing the rituals of religion was seen as not just practicing a ritual but communing with their divine family. Most commonly the pharaoh was the god Horus in his various aspects, though in the Second Dynasty one pharaoh Peribsen took Set, and Seti I and Seti II were both also dedicated to Set as late as 1197 BC. This is because Set was originally a protector of Ra the sun god and only later versions of the mythology turned him into an antagonistic god, specifically after invasions by the Kushites from the modern state of Sudan in 744 BC and the Persians in 525 BC. The change seems to be because Set was traditionally seen as the god of foreigners. And because of the antagonism towards external invaders Set became the murderer of the god Osiris, who represented the Nile, cutting up his body to prevent his resurrection and challenging Horus, the traditional god of the pharaohs, for rule over the land bordering the now godless Nile.

Now rule by a personification of a deity raises some interesting problems and possibilities. The most obvious is what does society do when there are failures? We have mentioned that Egyptian history is divided into unified Kingdoms and divided Intermediate periods. There are three Kingdoms; the Old from ~2600 - 2181 BC, the Middle from ~2134 - 1690, and the New from ~1549 - 1069. Each kingdom was followed and preceded by an Intermediate period which was defined by division, infighting and in between the Middle and New Kingdom foreign invasion and conquest of the northern part of the Nile Delta. It is impossible for the pharaoh’s to have ruled perfectly, their governments to have been uncorrupt for up to five hundred years at a time, and for such a dynasty to suddenly collapse into infighting.

As with Rome there was a long period of gradual disintegration of trust, respect, and rulership. It is difficult to generalize about such a long period, but we have to keep in mind the impossibility of perfect rules.

So, what does a society do when a god king inevitably goes wrong? How is order restored or maintained? How does such a system manage the inevitable variations and difficulties? How does it pass rulership to a new dynasty of rulers? There were just over thirty dynasties of pharaohs before the Macedonian conquests cut the cord of at least nominally native dynasties. One of the instruments of inheritance and order was the goddess and concept of Ma’at.

This goddess was the first born of Ra. So, the first ray of sunlight was this goddess, whose name meant ‘right order.’ She and the concept she embodied was absolutely essential for Egyptian religion and social structure. She was the thread that held the peace of the world together and when she was disturbed or violence was done to her, be it a peasant revolt, a corrupt official, or a tyrannical pharaoh, war, strife, disease followed. Disturbing Ma’at was a dangerous activity in Egypt, one that went against the natural and divine order. The importance of Ma’at can be seen in an interesting series of events in the New Kingdom. If the Old Kingdom is the kingdom of pyramids, the Middle Kingdom is the golden age of art, and literature, with the New Kingdom being the time of greatest Egyptian military and diplomatic dominance. However, this period of military dominance and expansion came out of an Intermediate period that was one of the most troubling for the Egyptian sense of self.

The Coming of the Hyksos and the Crisis of Ma’at

At the end of the Middle Kingdom a people, known as the Hyksos, settled into the Delta. There are competing theories as to who exactly these people were, with the Greco-Egyptian priest Manetho viewing them as invaders and conquerors but modern Egyptologists question this interpretation. The modern scholarly consensus is of a more gradual migration of people into Lower Egypt as the Middle Kingdom began to disintegrate, and possibly of a sort of mercenary relationship between the two peoples. Until the Hyksos began to take more and more power as the native Egyptian government became increasingly ineffective.

Now this theory cannot rule out violence and there was almost inevitably violence that broke out, namely as the Egyptian power receded and the Hyksos waxed. Wars were likely fought between the two until the Hyksos had conquered most of Lower Egypt and forced the native government to move to a new capital of Thebes.

The Hyksos rule over Lower Egypt began sometime during the Thirteenth Dynasty which lasted from 1803 - 1649 BC and would not be effectively challenged until the Eighteenth Dynasty which was founded by Ahmose I at some point between 1570 - 1544 BC, various dates are given by out sources and these dates have been narrowed down by a radiocarbon dating of his mummy along with the consistent reporting of his reign lasting twenty-five years across essentially all of the relevant sources. So, the Hyksos ruled the Delta for over a century, and it would take the first five pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty to finally reconquer all of the Hyksos land. And it is that fifth pharaoh that is so interesting and had to rely so much on the goddess of Ma’at, because she was a woman.

The God-Queen and the Performance of Gender

Now a female pharaoh had existed before but was not a positive reign. Sobekneferu ruled from 1806 - 1802 BC after her brother had died. She would die without producing a male heir and her death would signal the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, and it was because of this that the Thirteenth Dynasty had taken control. This was when the Hyksos had begun to truly encroach and challenge native Egyptian control. So, in the Egyptian view, already misogynistic, the Hyksos had been allowed to conquer because of the weakness of a woman and now a woman again was wearing the pharaonic crown. This was clearly a violation of Ma’at, despite her gender it was obvious that she would not bless another of her gender to rule Egypt.

So, when Thutmose II, died the new ruler, a woman named Hatshepsut, must have known she had an uphill battle for stability. For once it helped that the Egyptians had incestuous and complicated family relationships. Thutmose II was both her half-brother and her husband, both of them were the children of the previous pharaoh Thutmose I but they had different mothers. So, she had direct descent from the previous pharaoh and a marriage. She had legitimacy of descent and marriage on her side.

She also had something that Sobekneferu never had, a male heir, Thutmose, had a son by another wife who was not Hatshepsut. However, the future Thutmose III was only two when his father died and despite the insanity that is the Egyptian view on marriage and proper degrees of relationship between pharaohs it was not appropriate to have a two-year-old pharaoh on his own. Both he and Hatshepsut would rule jointly but for the first twenty years, until her death in 1458 of probable bone cancer, she was the main power on the throne.

There is evidence from statuary and inscriptions that by the seventh year she was considered a pharaoh in her own right. Her name was put on monuments, she had statues made of her and Thutmose, and she built temples.

Now her inscriptions and statues are interesting creations as they are forced to use the traditional iconography associated with pharaohs, which is all male. So, in her statuary she will sometimes have more developed breasts as a marker of her femininity, but she also is depicted with the pharaonic beard and in traditionally male dress. It is the same face across the statues, but the Egyptians struggled to incorporate the female body into their art depicting the ruler, because the art demanded that the ruler be male. Same with the grammar of her inscriptions, they still use female pronouns to describe her, but the titles remain gendered male. Now scholars have repeatedly noted that this seeming fluidity with gender in Hatshepsut should be understood as symbolic and ritual and not that Hatshepsut the individual experienced herself as androgynous or gender fluid. This was a function of her society struggling with the acceptance of a powerful and successful female ruler on her own terms. And Hatshepsut had to put their mind at ease, she could not be seen as disrupting Ma’at. She walked a fine line.

And so, in some ways she had to overperform her pharaonic roles and masculine traits. She became one of the most accomplished pharaoh’s of all time; massively expanding trade, securing borders, fighting the last vestiges of Hyksos power, and building temples. She did everything a great pharaoh should do and then more. And then she turned to the problem of Ma’at the goddess.

She had already renamed herself ‘Amensis,’ meaning ‘Wife of the God Amen,” Ahmen being an aspect of Ra and the patron deity of the New Kingdom. So, she was claiming to be the personification of the goddess Mut, a moon god and mother goddess of Egypt. So as most other pharaohs had claimed to be the father of Egypt, she was their mother. And her first child then would be the goddess of Ma’at. She was playing into the traditional imagery as Mut also wore the pharaonic crown and now how could she disturb Ma’at when she was her mother? A daughter rebelling against her mother would clearly be a disruption of Ma’at, and so the goddess could never be disturbed by her own mother taking the throne.

Putting the Divine House in Order

Hatshepsut had used her unique position to her advantage. But she still needed to highlight her special relationship to the goddess Ma’at, and so she decided to give the goddess something that she had never had. It was a special gift from a mother to a daughter, a house.

One of the three temples to Ma’at was in all likelihood built under Hatshepsut. Before the New Kingdom Ma’at had never had a separate temple, she had always shared space with other gods. She was in a corner of a larger temple, respected but never center stage. But the New Kingdom and Hatshepsut in particular brought her to center stage. She was now a goddess to stand on her own, the daughter of the pharaoh. This was likely a reaction to the return of Ma’at as a principle after the reconquest of Egyptian land from the Hyksos.

This was an attempt to mark a separation from the failure that had come before and had required decades of war and chaos to end a foreign occupation. And to add to this one of the major shrines that was incorporated into Hatshepsut’s funerary complex was a shrine to Ma’at. The murals on the walls depict the process of Hatshepsut being born. Claiming that she was personally shaped by the goddess Mut, whom she becomes the personification of upon rising to the pharaonic crown.

So, in death, in this new transition Hatshepsut gives up the personification with Mut and becomes a sister to the goddess Ma’at. Hatshepsut had become the exact reflection of the previous female pharaoh Sobekneferu; becoming order and not chaos, a restorer not a destroyer. It was a brilliant reign that set her half-son up for brilliant military conquests where he conquered from the Delta to the borders of modern-day Turkey. Her restoration of the kingdom also allowed the kingdom to survive Akhenaten and his monotheistic experiment, which rocked the kingdom as its basic principles of religion were attacked by the person who was supposed to be their god king. Akhenaten could have, in a more unstable kingdom, been the sign of the start of a new Intermediate Period but he was not. After his death he was replaced by his own son who changed his name to the more traditional Tutankhamen. Akhenaten being the fifth pharaoh after Hatshepsut, and Tutankhamen being the sixth.

Erasure and the Romanticism of Legacy

As Kara Cooney argues; Hatshepsut is "arguably, the only woman to have ever taken power as king in ancient Egypt during a time of prosperity and expansion."5 However, despite this and her achievements she was still a woman in these times and her accomplishments were largely publicly erased after her death. It is difficult also to definitively say that she took power herself and on her own initiative or if she was placed there by the powerful male power brokers of her time. We have surmise that she did have a deep desire to hold people and not to be pushed aside because of not only her accomplishments but that she survived and remained in power after Thutmose II came of age, and even when he was placed at the head of the army and became the single greatest military pharaoh that Egypt has ever produced. Even greater than Ramses II because Ramses was largely defending Thutmose’s conquests from invasions rather than expanding in any meaningful way. There is academic debate over which pharaoh was the one who began to erase Hatshepsut from the record, private inscriptions still remained, it was mainly public ones that were destroyed. This has led the Egyptologist Donald Redford in a touching if possibly too romanticized way to ask of the deletions;6

“But did Thutmose remember her? Here and there, in the dark recesses of a shrine or tomb where no plebeian eye could see, the queen's cartouche and figure were left intact ... which never vulgar eye would again behold, still conveyed for the king the warmth and awe of a divine presence.”

But whether or not her half-son felt genuine love and affection towards his godly mother the consensus in the scholarly community has shifted to the idea that it was actually Amenhotep II, Thutmose’s son and co-ruler at the end of his reign. Amenhotep II did not have the legitimacy that Hatshepsut and Thutmose did being the son of a minor wife and not the first born. It also might be indicative that he did have a royal consort for his whole reign, Tiaa, but she was not elevated to the standard title of Royal Wife until after her son Thutmose IV came to power.

This seems to indicate an even greater discomfort or fear of female usurpation of power in Amenhotep’s reign than Thutmose III who willingly shared power with Hatshepsut. Amenhotep also seems to have claimed credit for many of the developments that are properly attributed to Hatshepsut.

Now it is important to note that this erasure that took place was not complete, and seems to have been mainly public proclamations, unlike the erasure that took place after Akhenaten’s reign and his experiment with monotheism. But it is still important to note how the accomplishments of a female ruler were absorbed into the legacy of a male ruler; this is not a new phenomenon that only came about in the modern age.

Women have been there since the beginning, wielding power when and where they were allowed, but often forced back into the anonymity of the servants of a Regency novel. We should not be surprised that we have not properly acknowledged women and their role in the social and political order. But now we have hit on some of the important developments of Egyptian culture and civilization and next time we will move onto the people who began to write the next chapter in the rulebook for imperial rule. Sargon and Hammurabi had written chapters on conquering and law codes, but the problem still remained of how to stabilize vast holdings which contained varied and disparate people.

Oh, there’s the bell…

DUMÉZIL, GEORGES. 1935. “FLAMEN-BRAHMAN.” Annales du Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque de Vulgarisation 51.

C. Grottanelli, Ideologie, miti, massacri. Indoeuropei di Georges Dumézil, Palermo 1993, Benjamin W. Fortson, Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2004)

Now of course the Egyptians are not special in doing this. Many cultures and societies did not orient their maps towards magnetic north and there is a whole subset of discussions about how the orientation of maps tells us quite a lot about the importance that different societies placed on certain geographic features. Islamic maps will often be orientated towards the direction of Mecca, and Western maps would often be orientated towards Jerusalem, so that the holy city would be at the ‘top’ of the world in either religion. There is actually a fantastic general history of all of European history that purposefully orientates all of its maps this way as a way to change the reader’s perceptions of European space and realize how little they know about certain areas because they are focused on different spaces.

Green, Peter. 1998. Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient History and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cooney, Kara (2018). When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt.

Redford, Donald B. (1967). History and Chronology of the 18th dynasty of Egypt: Seven studies.